|

The Contralto

Rev. Charles Maloy, C. M.

St. Joseph's Parish, Emmitsburg, Md.

Chapter 16 | Chapter 25 | Chapter 1

The one labor question confronting the directors at the opening of the factory took the form of whether married women

should be employed. It had been permitted in the venture of the pastor now on the foreign mission, and many thought the new regime would tolerate,

perhaps encourage. The Professor set his face against such procedure, holding out stubbornly in the meetings, declaring the place of a woman with a

family was her home. Finally, he became quixotic, suggesting the instituting of a fund out of the earnings for such women as needed help in the rearing

of their families. Peter Bucket quietly pointed out that this was an adopting of the "something for nothing" principle, and he dropped it. His stand

against the employment of mothers was not weakened, however, he protested in a warm speech: "God knows it is bad enough that the change in economic

conditions necessitates us to supply work for the young women of the town, to take them from the shelter of the home, but we shall not, with my

approval, strike at the fountain-head of society; we shall not drag the mother from her duty of nursing the hopes of the future." Grizzled fathers of

families listened to this visionary stripling and voted his will in the affair, while Mrs. Hoke, having heard he was the author of the regulation, took

it as aimed at her, who had no children old enough to work.

The night before the formal opening, a banquet was held, in the part of the building that was to serve as a stockroom,

to which all the men of the town were invited. The Annan clique was not present, but Father Flynn was there and graciously responded to a toast. He told

of the interest the College had always taken in the welfare of the town, pointed with pride to the fact that Mr. Seabold was an alumnus of "our

institution," prayed fervently for the continued residence of Mr. Galt amongst us, and resumed his seat without evoking any salvos of applause. The

editor, acting as toastmaster, supplied the Father's omission, bringing down the house by introducing the source of inspiration of every work for

Emmitsburg uplift —the Professor. The crowd cheered to the echo as he arose and, a glass of mountain water in band, began. He modestly disclaimed the

encomium of his chief, declared himself indebted to the village and its inhabitants for his renewed health, and then riveting Father Flynn with his

eyes said: "Here's hoping that He who is the author of every good work shall bring this one to a happy finish." He drained his glass of water, while the

others drank their champagne to a toast which most understood not.

Vinny Seabold wrote full accounts to New York, telling of his care for the welfare of the working girls, his little

schemes through which they should retain their self-respect. She had teamed that it was by his direction they were advised to come to the factory

dressed neatly and one meeting them would imagine they were stepping out of an office building in some large city. Marion treasured the letters and

wondered how long before the soul of her lover would permanently emerge from the last layer of thought-dust.

Vinny, having learned from her father, who lately relaxed his policy of silence with his oldest daughter, that the

Professor had a plan to harness the mountain stream over which he had ferried the party, for the generation of power for the factory, asked him to walk

out and explain the engineering problems involved. They were a goodly pair as they strolled along, the girl a picture in her new found strength, bowing

and smiling at all they met. Mrs. Hopp hailed them as she came out of Annan's store and there was an unusual bitterness in her denunciation of Peter

Burket for giving up the grocery business, making her deal with a band of swindlers. Further down the street she accosted Uncle Bennett.

"I don't like that for a cent," pointing her thumb over her shoulder at the figures of the young people, "Marion's

gallavanting around New York, leaving him go eat his heart out here and perhaps to be caught by someone else. Not that Vinny isn't all right, but I've

picked Marion for him."

"Oh, I don't know," laughed the old man, "I'm a sort of Presbyterian in those things, though I wouldn't let Whitmore

hear me say it. I kind a believe they're fixed without us. If Marion is to have him, she'll get him in the long run."

At the old mill-race he explained to the girl the principles of his scheme, the installation of the wheel and the

dynamo, his professorial air being more interesting than the mathematics involved. He could not but remark his absorption in the task of exposition,

the fire in his eyes, as he hastily sketched the rude outlines of the work required, on the back of an envelope.

Old "Troxell' mill & race South of Twon as noted on 1797 mape of Emmitsburg area

(Click on map for larger version)

"How long shall it take to carry out that project?"

"It is not time, so much, as funds we need, perhaps next spring we shall be in condition to begin."

"That's good, you will be with us another year."

"I don't think so, I am not necessary for this, in fact I may leave at the beginning of the next school term."

"Are you going back to teach?"

"I am considering it," fingering the letter he still held, "I am not yet dead in the educational world; read that please."

It was a letter from the dean of the faculty of philosophy, in which he was gently scolded for hiding from his friends

and for appealing for help through official channels when the dean would be only too pleased to obtain him a position without the usual red tape. There

were several places to be had for the asking, he must write and let him know his preference. Vinny handed the letter back without comment, the odor of

the wild magnolia filled the air, the girl coughing as though oppressed with its richness.

"I go to New York day after tomorrow; Daisy will be home for her spring recess; I am coaxing father to let her come,

she has never seen the big city. Shall you join us?"

"Yes, the Baby can act as chaperon."

"And will prove more tolerable than our last," smiling.

That afternoon found the girl at her escritoire, penning a communication which brought thought furrows deeply to her

fair brow. It told Marion of her contemplated visit, with no mention of her companions, but it also told of the letter from the university, and her

fears that Emmitsburg was about to see the last of its redeemer; she felt sure he was going back to teach. This was read in due season and cast a cloud

over Miss Tyson's hitherto imperturbable outlook. She had gone too far in her policy of aiding him to find his soul. Her measures were too strong for

his budding love; in trying to force it she had perhaps killed it. Though Vinny confessed to having given him her address he had not written; he was

egoistic and he was proud beyond question. In her absence, thought dust plus his interest in social regeneration work had dimmed his vision and longing

for her. While he was sickly she had appealed to him, he had wanted her, but now he was grown strong, his first love had asserted itself, he would go

back to his abstractions in which she would figure as the remembered episode of a holiday. She was in a blue funk when Mrs. Halm joined her:

"We are to visit Mme. Tachereau today, dear." "Oh! I am tired of this round of scale singing," wearily.

"Why, what is the matter, child?" amazed at this change of humor, for Marion had found great fun in the visits to

studios.

"I haven't any voice, they are all bluffing just to get my money, they are making a fool of me."

"My poor child, you are not well this morning; all the experts have held out the greatest encouragement to you."

Her only reply to this was a fit of weeping during which the matron gathered her to her arms, which had never known the

embrace of a child of her own, yet were motherly in the extreme. After a few moments of coddling the girl was soothed, her ironclad resolution melted;

she told her companion everything. It was never her intention to take up a stage career, her coming to New York was a ruse to bring him to his senses,

and now he had forgotten her, all owing to her own foolishness. After perusing the letter, Mrs. Halm took a decidedly more hopeful view of the

situation, even hinting her surmise that from some hidden tone in Vinny's announcement, there might be a surprise in store for them.

It was not difficult for the Baby to wheedle the father into granting his permission, and it was an excited party that

waited for Mr. Gelwicks to bring his donkey-engine out of what was dignified as the round-house on a glorious Monday morning. The mother was there to

give last instructions for the guarding of her loved ones and Mrs. Hoppe to ask her boy to look up Esther in New York and report on her work in the

theayter. The genial conductor after consulting his great silver watch and declaring railroad like time and tide waited for no man (a remark which was

as much a part of his order of day as his cheerful smile), there was a general hugging and kissing bee in which the Professor shared Mrs. Hopp's

generosity, and the saucy engine puffed away.

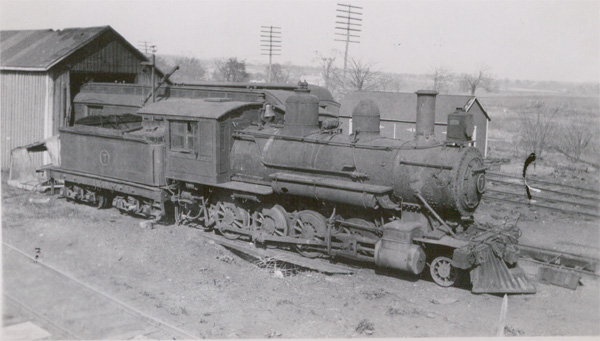

Dinky at ERR Round House

There was little to interest the child in the first part of the route, she had travelled it before; the time was spent

in answering questions about the great city. The Professor determined it should be a memorable trip for her; at Philadelphia began a lecture on

revolutionary history mixed with stories of college days suggested by the minarets of his old university. Stepping on the ferry, the grip of the

metropolis laid hold upon the tomboy, entertainment became easy. She announced with a stamp of her foot there would be no cabs, she must have her first

ride in the subway. They went under the river and as they came to Bowling Green, he invited her to stand at the door of the car to see the water, as

they passed through. Her look of injured innocence as they reached the other side and she realized he was teasing, was condign punishment; from that on

he was sincerity itself. At Forty-Second street, Vinny took command ordering him to put them in a taxicab and give them the name of his hotel.

They were gone; he sauntered into the place, which he best remembered as the scene of a bad quarter of an hour he had

given the house detective while celebrating a football victory. He smiled, quoting to himself the pedant's poet:

"To fill the cup and in the Fire of Spring, The Winter garment of repentance fling," he felt no inclination.

On the way up town, Daisy had conned her lesson, that the Professor's presence in the city was to be kept from Marion,

entering with a will into the scheme, for she had divined that Miss Tyson was in some way not playing square with her beloved friend. The look of

disappointment which clouded Marion's face when she saw they were alone confirmed the child's suspicion and she enacted her role of deception to a

finish. A call to the telephone caused Vinny to demur at Mrs. Halm's proposal that they go out, and in a few minutes the Professor was ushered in. And

oh! for the psychology of the female sex, how incomprehensible its methods, how its ways are past finding out! Marion received him with the least

visible flutter, manifesting symptoms of headache, when he proposed a theater party. The tomboy was not to be denied, however, so she sacrificed herself

to the wishes of the child.

There was no private converse between them that evening. Daisy felt the party was for her, she monopolized his

attention between the acts, seeming to think he should know everyone in the audience, as he knew all the French waiters in the restaurant at which they

dined, for all smiled in recognition, when he addressed them. When the ladies were about to retire, she read Marion a lesson in terms containing no

ambiguity, ending with a threat amazing in its straightforwardness. In her protocol she gave Miss Tyson until the next night to come to terms, as she

had paved the way by telling him the truth, had plainly assured him Marion was in love with him; in the event of any more bluffing she would take him

back to Emmitsburg and everything would be up.

A ride through the Park, visits to the Museums, a spin up Riverside Drive to the Tomb and dinner after, made all

desirous of a quiet evening, which was spent in the apartment. Mrs. Halm retired early; Daisy cuddled up on the sofa picked out places of interest from

the guide; Vinny played softly. For months Harry had pondered his plan of coming to a final understanding with this girl. He had once thought to embody

it in a letter, but had waited, telling himself he could state it better verbally. He now lighted a cigarette determined his procedure would be coldly

rational. When they were seated he said:

"Well?"

"Well?" echoed the girl.

"What is the verdict of the maestros?" which was not at all what he intended to ask—he knew from Mrs. Halm.

"Fairly favorable; they are pretty well agreed that I have a voice."

"When do you sail for Europe?"

"I must consult father and mother."

"When do you return to Emmitsburg?" he was getting farther away from the cool, rational process.

"Any time now; we were thinking of packing when Vinny arrived. You are going back to teach?"

"I am considering it, that is, if I determine to take up again the noble work of 'brat-walloping.' "

"Why don't you 'gird up your loins, seek your kind, and do a man's work in a world of men?' "

holding up two fingers, a trick he had taught her to signify quotation.

"The which demands a man's man."

"And the which you are."

Were right and wrong the simple, easy matter of selection the catechism tells us, how morally strong each of us would

be! There may be souls for whom the life of conscience is a promenade down a broad avenue at each corner of which glares the arc-light of one of the Ten

Commandments, where no dark shadows of doubt or hesitation lurk. It was not such for the Professor, whose eyes were holden by the scales of too much of

the so-called modern education. Marion endeavored to make him see, calling the roll of honor of the few successful opera stars, giving him statistics of

the young women, who go year after year filled with high hopes, only to return dire failures. He would or could not see his course, time sped without

his courage, to leap in the dark, reaching the sticking point. He rose to leave, Vinny turned from the piano, the three looked to the sofa where the

baby lay curled up on the cushions fast asleep. He gazed at her for a moment, then lifting one of the straggling curls, he pressed it to his lips and

tip-toed from the room. Marion started after him with outstretched arms but paused.

The awakened child asked sleepily: "Did you fix it?"

"Not yet, dear."

"That settles it, we go home tomorrow."

Though the morning saw repentance in her resolution the tomboy afforded no more opportunity to Marion, who in her

judgment deserved none. Esther was looked up, her turn at a Music Hall was witnessed and a supper with her as guest after. Mr. Webb's evening train

brought them home, the Emmitsburg Cornet Band was not at the depot.

Chapter 27

Click here to see more historical photos of Emmitsburg

Have your own memories of Emmitsburg of old?

If so, send them to us at history@emmitsburg.net

|