|

The Contralto

Rev. Charles Maloy, C. M.

St. Joseph's Parish, Emmitsburg, Md.

Chapter 12 | Chapter 11 | Chapter 1

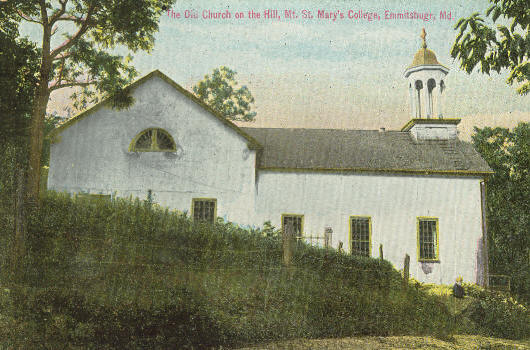

Four o'clock that afternoon found the tourists seated on the terrace at the side of an old church (old St. Mary's

Church) which had watched

over the destinies of the mountaineers for more than a century, a long time in this newest of civilizations. Built well up the mountain it told of the

psychology ruling the first spiritual shepherds in these parts, the days when religion demanded sacrifices from its votaries and reared its temples as

near as possible to Heaven. Love of ease had effected the dwellers in the territory to the extent of erecting a newer church (St.

Anthonys) more near to the high road,

and this one remained a mere place of pilgrimage from devotion or curiosity.

Old St. Mary's Church on the hill

The climb had been laborious, especially for Miss Seabold, who insisted, however, that the party go on despite their

solicitous protests in her behalf. Her fighting spirit was a revelation to the Professor, who mentally noted it as an important asset in her struggle

for health.

Mrs. Forman performed her duties of chaperon-age almost too zealously. She was not a native of Emmitsburg, having come

thither some years before when her husband elected to supply its inhabitants' demand for store teeth. She was a dainty little matron somewhere

in the thirties, possessing a girlish contour and disposition, a fair mental development, and an admixture of the harmless gossip sufficient to make her

company not disagreeable. None considered her of enough importance to criticise, though for that matter even Emmitsburg would have had difficulty in

finding anything to carp at in her very uneventful life. She lived in the reflected glory of the dentist, never expressing an opinion that was not

immediately backed up by the authority of "Hus," her pet name for the partner of her joys and sorrows.

On the walk up the mountain, she monopolized the Professor's company, shooing the two younger women ahead as though

they were children in pinafores. The one topic of her discourse was the failures of her husband in the various side ventures he had undertaken to

increase his financial rating. When each point was exhausted she interjected an entr' act rather disconcerting to her companion, as it consisted for the

most part of personal allusions or veiled criticisms of the other ladies. He found it hard to deal with observations like the following:

"Do you know, Professor, you have the most beautiful hands I ever saw? But, of course, you do; you have been told it a

thousand times I am sure. However, I should think you would be more careful.

I have noticed you playing ball with the boys, and it worried me lest you injure one of your fingers."

Such insouciance rendered him speechless, for Mrs. Forman's assurances to the contrary, he had never before heard any

remarks on the beauty of his hands. He also found difficulty in responding to this one.

"Don't you think Vinny and Marion, two dears? I do hope they get good husbands, especially Vinny. Marion is the kind

who can take care of herself, but Vinny shall wilt if she be not kept in perpetual sunshine. Which do you prefer?"

His resources were taxed to find methods of keeping up a pretence at conversation, but luckily the chaperon was not

insistent on replies to her questions. With the several stops necessitated by the fear of wearying Vinny and the gathering of branches of the autumn

leaves which blazed around them, they reached the terrace, inspected the church, and seated themselves on the grass, a little bored with the persistence

of Mrs. Forman's solicitude for their present and future welfare. Almost in sheer desperation, the Professor broke in:

"Did you ever hear the story of Zeph Heyer's hill-climbing leg?"

"Zeph is one of our local celebrities," said Vinny. "What do you know of Zeph?" asked Marion, "did you ever meet him?"

"Zeph's history, or at least the part of it which

concerns his famous nether limb," answered the Professor, lying full length on the ground, his hat over his eyes, "was

related in my hearing in Gresser's tonsorial parlor on the occasion of a recent visit."

"Do tell us," purred the chaperon, adding in a quite audible aside, "I do so love to hear him talk."

"Zeph had just treated himself to a haircut and shave, the executioner being Mr. Fred Brown, Gresser's able assistant.

I had succeeded him in the chair when the serious chronicle was narrated by Mr, Brown." With a perfect reproduction of Brown's intonation he proceeded.

"Zeph was shot in the laig at Gettysburg and the doctors said the laig must be cut off. Zeph's father wouldn't hear to this and went to the hospital and

fotched him home. Doc Stauffer sot the laig, and do you know, he sot that laig for goin' up hill? One Sunday me and Zeph took a walk up Jack's mountain,

and do you know Zeph was ahaid most of the time goin' up and he had to wait for me. But comin' down it was the other way to, I had to wait for Zeph.

That there laig was sot for goin' up hill but it wouldn't work comin' down."

The narrative was greeted with hearty laughter by the younger women and a decorous giggle from Mrs. Forman. Harry

continued: "I suggested that Zeph have the other laig broken and sot for going down hill, then he would be a marvel of locomotion, but Mr. Brown failed

to see any humor in his own relation of facts, nor in my addendum."

"If we are going to continue our climbing, I had better have my laig sot for going up hill," said Vinny.

"You are almost as perfect a mimic as "Hus,' Professor; you have heard him?"

"Oh Piffle!" exclaimed Marion, and without warning she gathered her skirts about her ankles and rolled to the bottom of

the terrace. The chaperon screamed, Vinny caught her breath and when Harry sat up he beheld Marion sitting at the bottom laughing and inviting them to

follow. To cover the situation he likewise rolled down and lay smiling at her feet. As they arose she said, "I had to do something or die of ennui."

From the top of the knoll came an hysterical request for the time. Looking at his watch he told the matron it was a

quarter before five. This knowledge was greeted by an outburst from the little lady. What would they do? It was impossible to get back before dinner

(dinner was Mrs. Forman's name for the evening meal, though for Emmitsburg in general it was tea or supper), and "Hus" would be worried. Her anxiety was

not shared by the others who looked with amused faces to the Professor to extricate them from the quandary if such existed.

"There's a nice, quiet hotel at Fairfield about two miles from here; we could get something there," he suggested

tentatively.

"Yes, but Hus will be so disturbed."

"I shall call him up as soon as we reach a phone and give him assurance of our safety."

"Yes I know butó"

"Come on, Anita," said Marion, "we cannot get home before eight o'clock; we may as well make the best of it."

"I shall faint of hunger on the road if we attempt to walk back now," declared Vinny, with more mischief in her eyes

than he deemed her capable of.

Without listening to further protest, Vinny moved along the top of the terrace followed by the reluctant matron, while

Marion and the Professor walked at the foot.

"Don't you think we selected a delightful chaperon?" she asked.

"Her hero-worship of Hus is really beautiful,"

he answered apologetically.

"It might be offered at a higher shrine."

Instead of taking the road which led part way down the mountain before joining that running to Fairfield, the party, at

the man's suggestion, struck off through the woods for a short cut. The glance of amusement that flashed between the girls was remarked by him though he

failed to comprehend its significance.

The sun was setting in a blaze of glory, as seen through the gap, which any artist reproducing would earn for himself a

high place in the most advanced school of impressionism. The chill air caused the ladies to draw their light wraps about them. The birds chirped

sleepily, the evening breeze fanned the drying leaves of the oaks and chestnuts producing that weird rustle which serves as the requiem of dying summer.

The spirit of fun, having deserted them, failed to return under the efforts of the Professor and Marion, who walked in front holding back overhanging

boughs until the two in the rear could grasp them. The spell of descending twilight made conversation fitful, an occasional warning addressed by one to

the others' The matron wore such a lugubrious countenance that Harry was thrown into deep contrition at his want of tact.

Coming out of a clump of blackberry bushes they found themselves on the steep bank of the creek with no ford in sight.

The two younger women burst into laughter, the matron indulged a suppressed scream, while the Professor was momentarily puzzled, then asked:

"How far is the Fairfiled Road?"

"Entirely too far to walk," answered Vinny still smiling.

"What are we going to do now?" came from Mrs. Forman.

"Take off our shoes and wade," from Marion, laconically.

"Oh you're dreadful, Marion."

The Professor had already removed one shoe and was busily unlacing the other. In less than a minute he let himself down

the bank, his trousers rolled above his knees, and waded down stream while Marion warned him to look out for holes, the ripples in her voice denying

anxiety. Finding a place where the bank descended with a gentle slope he called his companions to join him. When they had done so, holding out his arms,

the two girls pushed the chaperon forward, and amidst protests her ninety odd pounds of humanity were safely deposited on the opposite shore. Vinny was

next and not such a light burden, for after her ferryage Harry was puffing audibly. When Miss Dyson's turn came she objected:

"You cannot carry my one hundred and forty, I shall wade."

"Come," he panted.

"It will be easier to carry me on your back." "Come," with a shade of pleading, and she settled herself in his arms her

hands clasped tightly around his neck.

Once or twice he swayed but could not believe it was the girl's weight which staggered him; their eyes meeting in

mid-stream, his heart stood still, and it was with a sigh of relief that he let her slip from his grasp on the opposite bank. Recrossing he started up

the other side before the ladies had fully recovered and were still smoothing out their rumpled skirts.

"Where are you going?" shouted Marion. "For my shoes and stockings."

"Here they are," holding them up, "I tied them to my belt."

While he was returning, Mrs. Forman pleaded that the escapade should never be told, the girls assuring her they would

have it written up in the Chronicle. The adventure restored their spirits and again conversation flowed lightly. The chaperon clung to his arm giving it

a nervous squeeze every time a twig crackled in the lowering dusk. The young women in the rear kept up a witty fire of remarks for a time, then

whispered softly and the Professor became suspicious of more mis-steps. They were excogitating a scheme of female revenge, and at length Vinny said:

"Anita, tell Professor about your escapade with the stuttering visitor."

"Hush, Vinny, not for the world."

"Tell it or I shall."

"You're mean, but I suppose I must tell it. It was an awful faux pas, Professor. Hus brought a stranger to call, who

stuttered spasmodically. Hus is a dreadful mimic and is constantly doing just crazy things. The gentleman was talking some time before a spasm of

stuttering overtook him, and when it did, I burst out laughing and shouted, '0 Hus! you cannot stutter as well as he can.' When I found my mistake I

thought I would die of shame."

By this time they had come out on the highway and saw the House (Bella Vista) a hundred yards further up the hill. They were

welcomed by the proprietor and his wife, and much to the surprise of the women of the party, the small son and daughter planted long kisses straight on

the Professor's mouth. Extricating himself from the embraces of the little girl he went in search of a phone, followed by Mrs. Forman. In their absence,

the younger women each gathered a child to her arms and began a catechism.

Old Emmitsburg Road i~ 1900 headed toward Mount St. Marys

(Taken approximately at the intersection of present Old Emmitsburg and Scott Roads.

The house in the picture was called Bella Vista)

In answer to questions, the children boasted of their long acquaintance with the object of inquisition, the boy

claiming with even greater emphasis intimate friendship with the Admiral and Buster, while the girl confided to Vinny that she was the Professor's

curly-headed sweetheart. The boy was already signed as a prospective player on the base-ball team and questions as to whether they kissed him every time

they met were treated as ridiculously superfluous.

Miss Dyson hugged the boy impulsively, who, hearing the Professor's footsteps, jumped from her lap, the girl's fat legs

at the same time kicking themselves loose from the folds of Miss Seabold's skirt. The wife of the proprietor took the ladies in charge, the children

dragging him off to his room, pelting him with unceasing questions. Toilets finished, he was found by the others turning the children inside out, an

operation consisting of catching their extended hands between their legs and pulling them under so that they were turned heels over head, landing on

their feet. At the dining room the party halted with the instinct common to all Americans:

"You should have a drink of liquor, Professor, because of wading in the cold water," said Mrs. Forman.

"Yes, do," seconded Vinny.

Looking at Marion, whose face did not perceptibly change, he said, "No, thank you, I never take cold."

The repast was served by a good-looking mountain girl, who, on bringing in the first course, bowed and smiled, saluting

the professor as an old acquaintance. The matron was mildly perturbed, being heretofore of the opinion that real society people never addressed anything

but orders to servants. Another shock followed when he thanked the girl for every service rendered. As the waitress withdrew, he began:

"I am always embarrassed by female waiters."

"Why?" purred Mrs. Forman.

"When at the university we sometimes ate where they worked, in fact I may say we always did from the middle of each

school month until the beginning of the following one. In the first days, our allowances looked to be of champagne capacity, but by the middle had

shrunk to a beer limit. Then we went to the `beaneries' as we called them, and were satisfied with coffee for our beverage. I always found it hard to

offer a girl a tip and whenever I could shunted the burden to the shoulders of the other fellow. On one occasion, a German student eating with me, I

told him to leave the pour kite under the vinegar cruet, while I went to the desk to settle the bill. My friend sounded a warning that could be heard

all over the place, attracting the waitress' attention, held up the coin so that all could see it, then planted it under the cruet. The occurrence like

so many other small things left an indelible memory."

At the conclusion of their pleasant dinner, the proprietor announced the team had arrived and the ladies met Bob

Crittendon in the hall with cloaks in his arms, while outside a three-seated carryal stood waiting. The adieus were given, the children getting a kiss

and hug from their friend, and preparations for departure were in order.

"Can you drive, Bob?" asked Vinny.

"Who, me? watch me."

"Then get in here with me, Anita," she ordered, climbing into the second seat before Harry could lend her a helping

hand. His aid was bestowed on the chaperon, then turning to assist Marion, he found her already seated. Bob began the descent of the mountain, the going

being so rough for a time that talking was discouraged; later the road became more smooth or the travellers more accustomed to the ruts, and Miss Dyson

asked:

"You love children?"

"Worship them," he assented as though he had been expecting the question. "Are not those two youngsters beautiful?"

"Another point," but the carriage was too dark for him to come at her meaning by looking at her face.

Nearing the toll gate he called to Bob to know if he had the change, the boy assuring him that he would fix it.

Suddenly a lantern appeared, the team halting as Bob's grinning face looked out at one side of the wagon.

"Toll House' at top of 'Toll Gate Hill'

(Taken from what is now the intersection of Old Emmitsburg Road & South Seton Ave)

"Clerical dooty" he shouted; the bar swung up, the team 'passed through. The ladies laughed softly, while the

Professor sought enlightenment.

"It's this way, Professor, you don't pay no toll when you're on clergical dooty. They know me and think I got the

Rector in here."

"That isn't honest, Bob," severely.

"They don't keep their old roads up anyway," argued the red-haired sophist; "they wouldn't pay for it if one of 'my

hosses broke his laig."

"You cannot convince a Emmitsburger that toll-gates are aught but evil institutions to be beaten whenever possible,"

explained Marion; "it's useless to argue."

The horses pulled into Main Street. All curtains were drawn but from behind them many pairs of eyes peeped out on the

unconscious party. Miss Seabold was the first to be dropped, Mrs. Forman electing to alight with her, so the Professor and Miss Tyson got down,

dismissing Bob. They parted, Harry and the girl sauntering towards her home. She was the first to speak:

"I learned a great deal about you today, and I'm proud of you."

"May I have the particulars?"

"No, you would not relish them, you would accuse me of flattery."

"I could never accuse you of lack of straight forwardness," with a quiet laugh.

"Good night, boy, and believe me you have more than a fighting chance."

He took her extended hand, the two standing for a moment gazing into each other's eyes, then the weakness he had

experienced in the middle of the creek came over him. With a squeeze of her fingers which made her wince he walked away.

That night sleep was long in coming, debate waged in his soul; the resolution made some time before and strengthened

after his recent illness, seemed now illogical; he determined the subject needed reconsideration. In the nervous semi-consciousness just before sleep,

which bothers some people, he found his hyperaesthetic mind recalling from Chamfort: "Le bonheur n'est pas chose aiaee; it eat tres di, cite de le

trouver en noun, et impossible de le trouver ailleurs." He had found it very difficult to secure happiness within himself, was it possible to find

it elsewhere? He fell asleep wondering.

Chapter 13

Have your own memories of Emmitsburg of old?

If so, send them to us at history@emmitsburg.net

|